Seligmann was fascinated by the few occasions in Le Corbusier’s oeuvre—no doubt in collaboration with his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret—when he hybridized these systems: several of the “pavilion” projects (Pavillon des Temps Nouveau, Pavillon Liège, and his last design, now called Pavillon Le Corbusier) used the notion of a superstructure beneath which smaller modules were distributed; the Villa Shodhan in Ahmedabad—often described by Seligmann as a “roll of the dice”—posed the same spatial organization in both plan and section, combining the Citrohan type with directional piers and an occasional Dom-Ino quotation. Shodhan and many of the more complex spatial productions were unified by what Seligmann identified as the “long dimension” in Le Corbusier’s work. This was in effect an organizational device involving diagonal vistas, so that the viewer might be aware of the boundaries of the structure’s entire spatial field, beyond the realm of the occupied volume. Seligmann would always employ a version of this in his works, such as with the diagonal visual “skewers” in the sections of the duplex units at Elm Street in Ithaca, in the Ithaca Center, and in the plans of the synagogues and the larger public buildings.

However, equally important to Seligmann were the spatio-structural importations from other, pre-modern precedents, most notably what he often described as “slits” and “slots” of space, essentially architectural caesuras. A prime source was John Soane’s Residence and Gallery at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where vertical crevices of space and gaps between lines of structure are used to produce avenues of circulation, objects within spaces, spaces within spaces, and structures within structures. This notion of spaces of articulation, some occupiable and some exclusively visual, was also central to Seligmann’s interpretation of many indigenous and non-Western precedents. He found it, for example, in many of the historic works in India, such as the Stepwell at Adalaj and the Complex at Surkhej, as documented by former student, colleague, and friend, Klaus Herdeg, and presented in 1967 at Cornell in the monograph and exhibition, Formal Structure in Indian Architecture. Throughout his travels, Seligmann was aware of the intensely concatenated spatial fields present in the bazaar complexes of cities such as Isfahan, as well as in the Mayan city plans circulated by Lee Hodgden at the time.

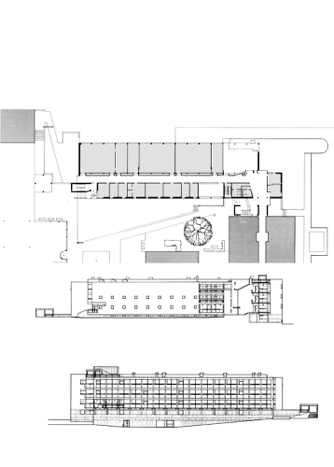

Similar to his characterization of Le Corbusier, Seligmann selected his structural systems for their spatial capabilities as they related to programmatic accommodations, but he was also very aware of the rhythmic values of structural systems—both real and implied—that when accompanied by cladding and fenestration, helped to construct a building’s overall cadences, providing its essential contrapuntal richness. For example, as with most of its neighboring structures, the Science Building II at the State University of New York at Cortland has a steel frame with brick exteriors and occasional concrete lintels. However, its use of these materials is distinctly different from that of the rest of the campus. The Cortland Science Building II might be understood as a virtual concerto, with its themes, variations, accentuations, and tempos.

v15ab&c_Science Building II, State University of New York, Cortland, 1966: entry plan, east elevation, and west elevation (from top)